Artificial intelligence is primed to explode in the face of the art world and it is perhaps time to remind ourselves what we want from a painting. The arrival of AI image generators raise fundamental questions – what values do we ascribe to art and how important are the thoughts and emotions that go into its making?

Image generators such as DALL·E 2, Midjourney and Stable Diffusion generate images from a short line of descriptive text and the images can be truly remarkable. No doubt some artists will run with the technology and create spectacular exhibitions in its purest form. Many will also argue that AI generators are just another tool for artists to use which is true – but a tool like no other. The equivalent of a brush that also offers suggestions, a brush that has ideas of its own.

We are at the beginning of the ‘intelligence explosion’ as expressed by mathematician I.J. Good, who in 1965 foresaw the moment when artificial intelligence begins to leave us behind. And creativity, the one element of human nature that helps to define us collectively, is the first to fall.

Post-war, most figurative painters still painted from life with elements from the imagination. In recent decades a huge shift has taken place and the collaboration with the model in the studio has largely been replaced with various degrees of working from photographs. With the arrival of AI, copying will become prevalent and will lead to a plethora of phantom paintings, works copied directly from AI generated images, indeed it is already happening.

My hesitation in celebrating the arrival of AI generated art is due not to a resistance towards a new technology (as many artists did with the arrival of photography) but because it will lead to another round of copying and a profusion of market-ready paintings with little or no substance.

As an example, the image below was generated in approximately ten seconds, following one written prompt – ‘Rembrandt still life rambutan painting’. This image could now be laboriously copied onto canvas (an easy task for any diligent painter or illustrator) and presented as an original painting, even though only two seconds of thought went into deciding what to write.

Still life with Rambutan, generated by AI

It’s not difficult to imagine art fairs peppered with such works (particularly with a surreal edge); where titles are an adjunct to instil a touch of meaningfulness. AI generators are continually copying and learning – and learning from some the greatest artists who ever lived. Prompt the system with an established painter’s name or upload an existing drawing or painting into the system and images with random compositional suggestions are miraculously generated. On the surface it seems wonderful, but a well-designed composition can drive a painting and lead the eye around a canvas to settle on areas of importance. In other words, composition is intrinsically bound to the content. With AI the user just needs to identify what appears authentic.

For many illustrators the impact of AI is likely to be substantial to the point of threatening their livelihoods. To rub salt into the wound, AI generators scrape the internet to create datasets containing copyrighted artworks to which illustrators are major contributors. It will be no surprise if we see the industry resort to some kind of verifying icon to indicate the human input of their work, enabling consumers to see which businesses retain artist-led creativity. For the art world, education and transparency in how works are realised is perhaps a better way forward.

The one thing a facsimile of an AI image cannot offer is ‘touch’, the physical evidence of the artist’s individual mark-making. This missing ingredient, which contributes to our general perception of what a painting is, will be the financial incentive that encourages many artists to copy AI images rather than exhibiting the pictures in their original format. A straightforward AI generated image would likely have little commercial value, but when enlarged and diligently copied and painted onto canvas it becomes a marketable commodity. Yet the copying process in itself adds nothing to the content of the work. Transcribing an AI image or photograph with a veneer of paint only changes its perceived status as an art object.

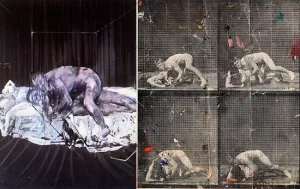

In contrast, artists such as Luc Tuymans, Francis Bacon, Marlene Dumas, Peter Doig and Edgar Degas have all utilised photographs but rather than being subservient to the original image their expressive interpretations allow their work to be transformative. And it is perhaps at the juncture between these two approaches that ‘appropriation’ lies.

Francis Bacon, Two Figures, 1953

A leaf from a book, Eadweard Muybridge, The Human Figure in Motion

When we encounter works by artists as diverse as Rembrandt, Alice Neel, Gwen John and Ellen Altfest we are witnessing both time condensed and evidence of their own encounter with what was before them, often combined with areas conjured up from their imaginations. There was no intermediary, no camera providing a ready-made image, no software to do the same. And so, what we see and what we ourselves experience is 100% Rembrandt and Neel. It is this aspect that I believe AI will erode further. As the market is king, we will see countless paintings copied from AI generated images and the source will not always be obvious. And many (not all) will be meaningless, the results of playing around with software without a sense of purpose.

I feel the art world is about to sleepwalk into another wave of copying as it did with the emergence of 3D scanning for figurative sculpture. 3D scanners and milling machines deliver homogenised forms without nuance. The only way we can differentiate between who made what is by subject matter/concept, the choice of materials and the publicity that surrounds them. One would never confuse Donatello’s David with Michelangelo’s David. Likewise, the impossibility of confusing the forms of Barbara Hepworth with those of Franz West, Elizabeth Frink or Giacometti. The fact that the art world embraced a copying process so eagerly is understandable as many artists have tried to bamboozle their audiences in order to mask the process behind how their works are made.

The ease of copying allowed the Old Masters to employ copyists and give apprentices the dull task of copying and enlarging the master’s drawings ready for painting. It is why students as part of their training were instructed to copy drawings first before moving onto the live model.

To understand fully it is worth pausing to revisit the copying process and why it ‘mitigates’ the presence of the artist. Copying is the practical component of making some pictures and during the Renaissance many studios also produced copies of their most successful works. Painting from an AI image, a photograph or a projection is quicker and easier than working from life because the camera or software has already flattened the image down to two dimensions. The artist does not have to grapple with transcribing a three-dimensional subject onto a flat surface.

The Old Masters understood negation. It is why Rubens, who ran a large workshop with assistants, charged considerably more for a work made entirely by his hand.

Some will look for similarities with tools and devices used by artists in the past and quote the wilder claims from David Hockney’s book, ‘Secret Knowledge’ which assumed widespread use of optical aids by the Old Masters. These points however will always have to bypass the consequences of diluting an artist’s input into making a painting. A symbiotic relationship exists within all paintings – why it is made and how is it made. If that relationship is knocked off balance by a prioritised financial incentive, then the painting itself becomes compromised.

When looking at a painting copied or based on a photograph, we can at least share the reference point with the artist. We are familiar with the pictorial characteristics of photography. No reference point exists when the original source material for a painting is AI generated. Did AI create the composition, the forms, the imaginative juxtapositions or was it the artist? Who served who? Each time an AI generator teases the user with multiple images, it is running ahead and the original prompt is quickly marginalised. The choice-based process diminishes the autonomy of the artist. The user becomes the shopper, having to decide which cake to choose and upon choosing one, more cakes arrive. Post production becomes adding the cherry to what has already been served.

The experience awaits us all, of responding positively and perhaps even emotionally to paintings that are merely copies of AI generated images. If we learn of their conception (and possibly our deception) how will we respond? Knowing that AI had led the way and effectively held the brush.

A large still life which I painted over many weeks in 2008 with two phantom still lifes generated by AI in under ten seconds from a single sentence.

So why does all this matter? So what if images are manually copied across from one medium to another. In one sense it doesn’t, as there will always be audiences who just want to look at pictures and have no interest in why they were made and what they may concern. However, it certainly matters if we want to hold onto what makes art precious in our lives, where the integrity of a work is paramount.

There is immeasurable value in looking at Velázquez’ startling depiction of Pope Innocent X and being aware that the artist stood before him, shared time with him and coached him into position. There is an appeal in discovering an awkward passage of foreshortening in a Freud painting. A passage that reminds us this wasn’t achieved quickly or without a struggle, that a human presence is imbued throughout such a work and which in turn enables us to connect with it in such a visceral way.

We must rely on a new generation of young figurative painters to kick against the prevailing culture of copying within contemporary painting, to take courage in the development of their own observational skills and personal mark-making. It is only then that we might once again be exposed to the connective power that artists such as Alice Neel and Paula Rego brought to bear.

AI offers an opportunity for everyone to create, regardless of technical ability. But we need to be mindful of how it plays out in the hands of the art market and how those results will inevitably shape what we get to see.

For me, I paint from life not because of the challenge it presents but because when I see images in my mind they never appear in a photographic form. Painting from life is as close as I can get to realising images as I first see them. There is no place for such thinking with AI.

Nicholas Williams, November 2022