Accompanying text for an exhibition of drawings – ‘Life Studies’ – Royal Cornwall Museum, 29/10/2018 – 23/12/2018

On Drawing and Intimacy

Thoughts on Nicholas C Williams’ Life Studies

Drawings are the most intimate of images. Laid between sheets of translucent tissue paper in the darkness of drawers, rarely handled, seldom viewed, intimacy is as much a part of their preservation as it is their production. This is heightened by the creating, conserving and viewing of the life study, the rendering of the human figure from the observation of a live, often naked model which encourages us to reflect upon what we often try to conceal: our relationships with ourselves and with each other; our fantasies, fears and frailties.

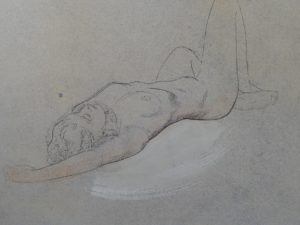

When the British painter and draughtsman Nicholas C Williams invited me to his studio to view his figure studies, I hesitated. Life drawings make demands of us as viewers that can be difficult to articulate, not least to the works’ creator, but they ask a great deal of the artist too. As Williams describes it, ‘Artists are at their most vulnerable when they draw because everything is revealed by their choice of subject, areas of attention, and mark-making.’ This is especially the case with the image of the human figure, that most difficult of subjects, which I find myself turning to for evidence of a mastery I know I will ultimately critique. The nude, that most exalted genre of Western art, is more often than not the image of the nubile, female body ‘mastered’ by the male artist’s gaze, which places artists like Williams and art historians such as myself in interesting positions. I thought on his invitation whilst looking at a reproduction of his Reclining Female Nude with Blue, a study in graphite.

At the centre of the sheet of toned paper, a naked woman lies on her back. The image is arresting because of the position Williams takes up in relation to her. Seated both lower to the ground and behind her, the view he chooses of her body requires him to foreshorten it, drawing not the form but the distortion that is seen by the eye when looking at it. Such perspectival trickery is immensely difficult, necessitating an absolute understanding of the methods by which the pictorial illusion of reality is achieved. Equally compelling is the quality of Williams’ line. Drawn almost entirely ‘on point’ with the finest graphite, the body materialises on the sheet through an outline that may run out but never wavers in its anatomical precision. The image would be exhausting in its exactitude were it not for the woman’s hair, described in an eddy of muddied watercolour, a brush mark the very opposite of the sharp graphite line, which is placed, to my surprise, at the centre of the composition. Applied to the sheet after the technical feat of the drawing itself, the mark, I imagine, took courage to make.

This is the evidence of the technical mastery and invention I look for in the work on paper, but it is not why I find myself returning to the image. The model’s legs are splayed, knees pointing to opposite corners of the sheet. The pose is an explicit one, or at least, it would be if the artist were sat where we might expect to find him, in front of the subject. Acknowledging our desire to see what is intensely private with the evocative swirl of the model’s head of hair, Williams decides, nevertheless, to sit elsewhere. The drawing is enthralling because it holds two opposing forces in the balance: the drive to observe, to know, to ‘master’; and the decision to turn away, to leave this most intimate area of the body to its subject.

I accepted Williams’ invitation to look at his life studies. In the half-light of his studio, I saw this sheet and a mere handful more – carefully-conserved drawings in pencil, graphite and sanguine with occasional washes of watercolour or gouache which were, I realised, distillations of many, many years of practice. Williams describes drawing as ‘a very personal and private practice’. It was a great privilege to converse with this artist on his deeply humane image of ourselves at our most vulnerable.

Gemma Blackshaw, Professor of Art History, University of Plymouth, August 2018.

About Drawing

Selected Drawings From The Royal Cornwall Museum

Drawing from life has remained central to my work for over thirty years. Early life classes at Richmond College gave me a solid foundation in drawing, continued since by working exclusively from life. It is the ongoing study of the Old Masters, however, that teaches us how every aspect of the human condition can be expressed through drawing the figure.

The drawings in the exhibition date from the seventeenth century to my own studies this year. Those I have selected range from preparatory studies and imaginary scenes (informed by working from life) to finished drawings. Decorative flourishes and affectations are absent, as they serve no purpose in conveying form or advancing an idea.

It is the meaningful dialogue with the subject that gives the Master drawings their inherent power. In Guercino’s depiction of Cleopatra, for instance, his line is confident and fluid, yet considered. The figure is primarily described through contour, with much of the paper left untouched. The rendering is kept to a minimum. The few lines under her breast follow form, as do those that gently wrap around the left of her abdomen. The drape that crosses her body acts as a device to enable Guercino to describe the slight foreshortening of her left thigh. As with any depiction of a partially clothed model (most evident in works by later artists such as Egon Schiele), it tells us immediately that this is not merely a drawing exercise, but something more open to interpretation.

Guercino imbues Cleopatra with her signature carnality, turning a simple assembly of well-executed lines into an engaging narrative. This crucial aspect of the drawing announces Cleopatra’s presence. The work is a riveting encapsulation of the principles that underpin great drawing. The challenge of bringing these principles together in a single intuitive response to the subject is why making a good drawing will always remain an elusive activity.

There was little information to accompany the images I found in the Museum’s collection; few clues as to their origin or context. It meant my selection was entirely about what is seen, not what is known. There are perhaps inevitable questions raised by an exhibition of the nude, and further questions, too, about the demographic of artists selected. The annals of art history reveal, not surprisingly, a scarcity of female artists – a scarcity diluted even further when looking for depictions of the nude, and further again when searching for such depictions in the drawers of a regional collection. Up until 1893, the Royal Academy denied women access to the life class. Such draconian attitudes had far-reaching consequences and still impact on shows such as this one.

While paintings urge you to stand back, demanding distance, drawings beckon you in. You have to come close. Great works are locked chambers of energy and time and nowhere is this more clear than in drawings. When you look at a particular line in a drawing that might be three or four hundred years old, you can actually see the speed of that line. It might be an eighth of a second from the initial touch on the paper to the end of the mark, but what you are looking at is time preserved, a moment documented from the past. What you cannot see or know is the time spent looking between the making of those marks.

For young figurative artists the ease of copying photographs is always a temptation, as the camera has already transcribed the three dimensional onto a flat surface. But much is sacrificed in the process; the camera acts as a disruptive intermediary between artist and subject.

Drawing the nude figure requires the deepest act of ‘seeing’. It’s never a detached act of observation, but rather one that is affected by the input and presence of the model. There is a central ethic of collaboration. With the immediacy of drawing, it is perhaps this one intangible element that working from photographs cannot provide, and can make looking at figure drawings so compelling.

Nicholas Williams 2018

Cleopatra, Guercino (Giovanni Francesco Barbieri), circa 1640. Iron gall ink on paper, 160 x 280mm © Royal Cornwall Museum