The Horse Hospital , Bloomsbury London is presenting an exhibition of new works by Nicholas Williams. The exhibition will coincide with Frieze week forming part of the Horse Hospital’s year-long programme to mark its 30th year as a vital and progressive venue for art and performance.

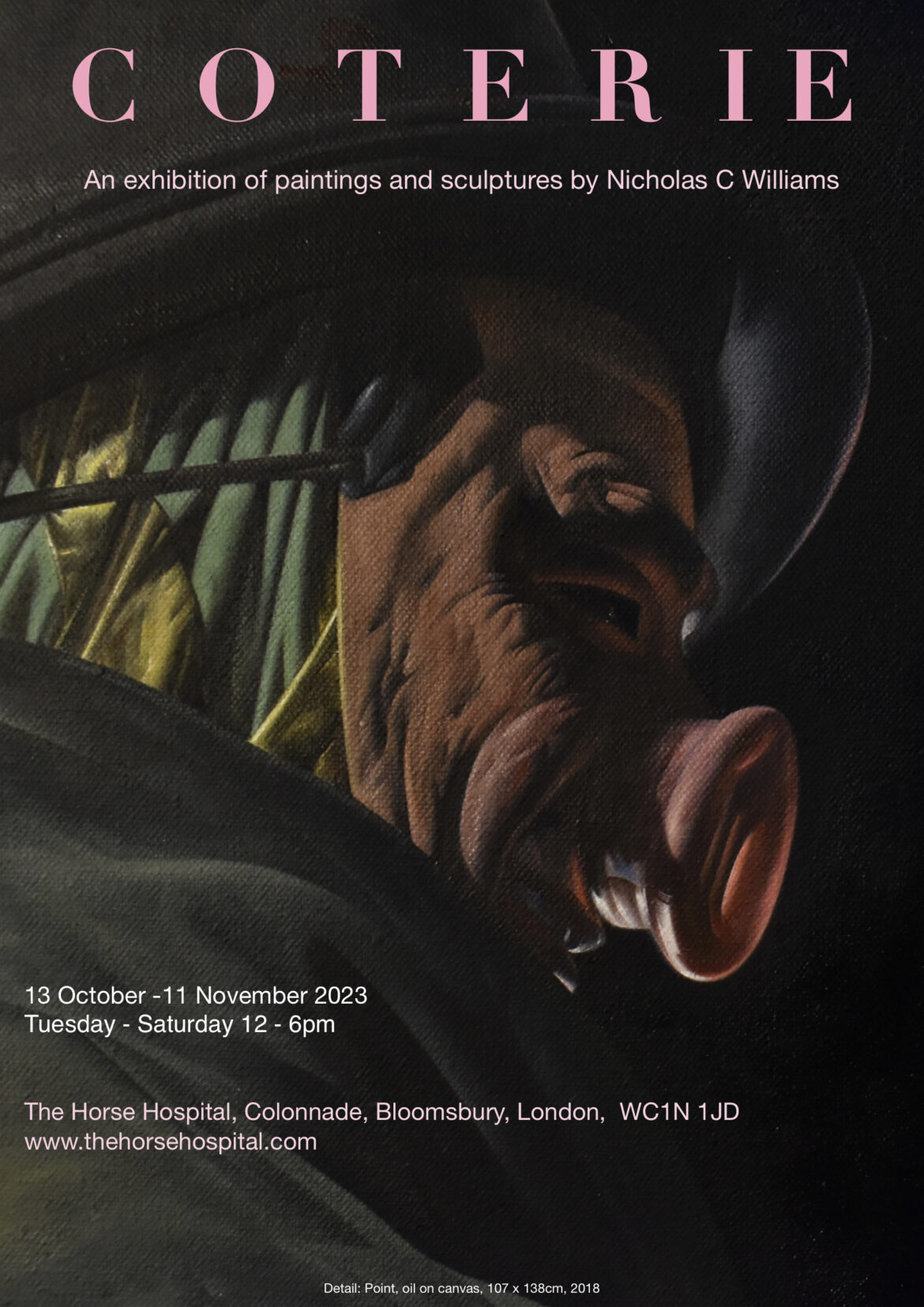

The show represents Williams’ first London solo exhibition in over thirty years. It brings together a group of paintings and accompanying sculptures – the physical attributes that inhabit a number of the paintings. The works are a response to a climate of hidden agendas, an opacity of power and the rise of conspiratorial dialogues.

Williams’ studio methodology draws on symbolism and methodologies developed by the Caravaggisti during the early part of the 17th century – of working direct from the model in a darkened studio and using light as a way to navigate through a painting.

Solo shows include the Russell-Cotes Art Gallery & Museum, Bournemouth; Royal Cornwall Museum, Truro and Liverpool Cathedral for the European Capital of Culture. Public collections include Bournemouth Central Library, Falmouth Art Gallery, Frissiras Museum, Athens and the British Museum.

Exhibition runs from Friday 13th October – 11th November.

Open Tuesday – Saturday 12-6pm

The Horse Hospital

Colonnade, Bloomsbury

London WC1N 1JD

https://www.thehorsehospital.com/events/coterie